The Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain Museum -- one of Brunswick, ME's, most-visited historical landmarks -- is situated on the corner of Potter and Maine streets, just up the hill from Brunswick's bustling town center, and across the street from Bowdoin College.

What many people today might not realize, though, is that this now-stately 2 1/2 story building began its life around 1825, as a 1 1/2 story Cape Cod-style house, with an adjacent ell and barn, at 4 Potter Street, about a quarter-block from where it now stands. It stayed there until 1867, when it was moved to its present Maine Street location by its owner: Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain.

Chamberlain bought the house in 1859, when he was a young Bowdoin College professor of rhetoric. He paid $2100 for both the house and the land. Here, he and his wife, Fannie Adams Chamberlain, raised their children: daughter Grace Dupee, and son Harold Wyllys. Chamberlain lived in this house until 1866, when he was elected to his first one-year term as Maine's Governor. During his four one-year terms, from 1866 to 1871, he would split his time between Maine's capital, Augusta, and Brunswick.

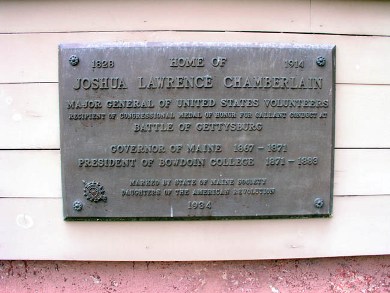

This is a plaque attached to the front wall of Chamberlain's home. It was placed here by the Maine chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution, in 1934.

Photo by David Williamson.

Do not use without his express written permission.

(In an ironic twist, one of modern Maine's most recent governors, Angus King, also lived in a house on Potter Street, and would not live in the governor's house in Augusta. He commuted between Brunswick and Augusta on a daily basis. Plus, when one compared the appearance of both men, they're strikingly similar in appearance. Plus, Governor King often quoted Chamberlain in his speeches.)

During that time, he felt his home needed a more prestigious location, which meant out on Brunswick's 'main drag': Maine Street. He decided not to buy a brand-new house, so he did the next best thing instead: he moved his present house, literally, to a plot of land bordering Potter and Maine Streets. He purchased this plot for around $1400. Then, using logs for leverage, and oxen for transport, Chamberlain moved the house -- and then had it turned 90 degrees, so it outwardly faced Main Street.

After leaving the Governor's office in 1871, Chamberlain was appointed President of his alma mater, Bowdoin College. He realized the position would require more room than the 'tiny' house could accomodate. While he could have bought another house, or even moved to the existing president's house at nearby Federal Street, Chamberlain instead decided to enlarge his current home instead.

Fortunately for Chamberlain, Maine's Midcoast area was a huge center for shipbuilding. In fact, the shipyard in the nearby city of Bath was one of the largest and oldest in the US. With that in mind, he obtained the use of railroad jacks, and shipyard cranes from Bath, and the house was raised 11 1/2 feet off the ground, and a first floor was was built beneath it. Chamberlain used an Italianate-style design for the entrance, and arched windows on the new south porch, which were glassed in.

Here's a side view of Chamberlain's home, showing the glassed-in south porch, which became a greenhouse.

Photo by David Williamson.

Do not use without his express written permission.

One of the more unusual features on the house is a decorative chimney at the front, emblazoned with a red brick Maltese cross -- the emblem of Chamberlain's beloved First Division, Fifth Corps, Union Army of the Potomac.

Here's a good view of the restored chimney, with the Fifth Corps emblem.

Photo by David Williamson.

Do not use without his express written permission.

The grounds on the west side of the house were the site of Chamberlain's extensive fruit and vegetable gardens. They contained stuff such as squash and asparagus, strawberry beds, grape vines and currant bushes. As a young professor, Chamberlain could often be seen in his shirtsleeves, working diligently in these gardens, before heading off to his Bowdoin College classroom. The flower beds contained plants grown in his greenhouse: the glassed-in porch on the Potter Street side of the house. He also had a purple martin house in the yard, and during the Civil War, he would write to Fannie and inquire how the birds were doing with their little house.

During a newspaper interview, years after the war, Chamberlain made a rather wry remark about all this major 'home improvement':

Here is a closeup view of the recently-restored decorative iron fencing, in front of Chamberlain's home.

Photo by David Williamson.

Do not use without his express written permission.

The yard itself has undergone many changes throughout the years. In the first years after its renovation and restoration began, a set of hedges sat on both the Maine Street and Potter Street sides of the house (which can be seen in the first photo on the page). Later research indicated, however, that a decorative iron fence fronted Maine Street. It was discovered that the original manufacturer -- based, ironically, in Alabama, given Chamberlain's wartime experience with Alabama regiments! -- still existed, and they still had the original fence mold. So, after an extensive fund-raising campaign by the Pejepscot Historical Society, the Maine Street-side hedges were replaced in 2004 by the restored iron fencing.

Another view of the restored decorative iron fencing.

Photo by David Williamson.

Do not use without his express written permission.

Today, the house is painted, as it was then: light cocoa-colored siding, dark chocolate-colored window frames and forest green mullions and transoms.

Here's a great view of the house's paint work.

Photo by David Williamson.

Do not use without his express written permission.

In his will, Chamberlain left the house, and its contents, to his daughter, Grace Chamberlain Allen, of Boston. After her father's death in 1914, Grace converted parts of the house into apartments. Before Grace's own death in 1937, she left the house to her youngest daughter, Rosamond Allen. Two years later, in 1939, Rosamond sold the house, in turn, to a Brunswick resident named Emery Booker, who then converted the whole house into seven apartments in total. These eventually became housing for Bowdoin College students -- who, as can be the case with college students, often left their quarters in a wreck.

Here's a nice overall view of the front of the house.

Photo by David Williamson.

Do not use without his express written permission.

Over the years, the house deteriorated, because of both age and neglect. It got so bad, in fact, that it was very nearly demolished. Thankfully, however, salvation came in 1983, in the form of the Pejepscot Historical Society of Brunswick. They bought the house from the Booker estate for $74,000, which was raised in a massive fund-raising effort. Since that time, the Society has worked diligently to preserve and restore this beautiful house. And the work continues, right up to this day.

NOTE: This Web site is Copyright © 1999- 2009 Pat Finnegan. All rights reserved. DO NOT use any written material, or photographs, without first contacting me in writing. If you do not do this, be assured that legal action will be taken.

THANK YOU!